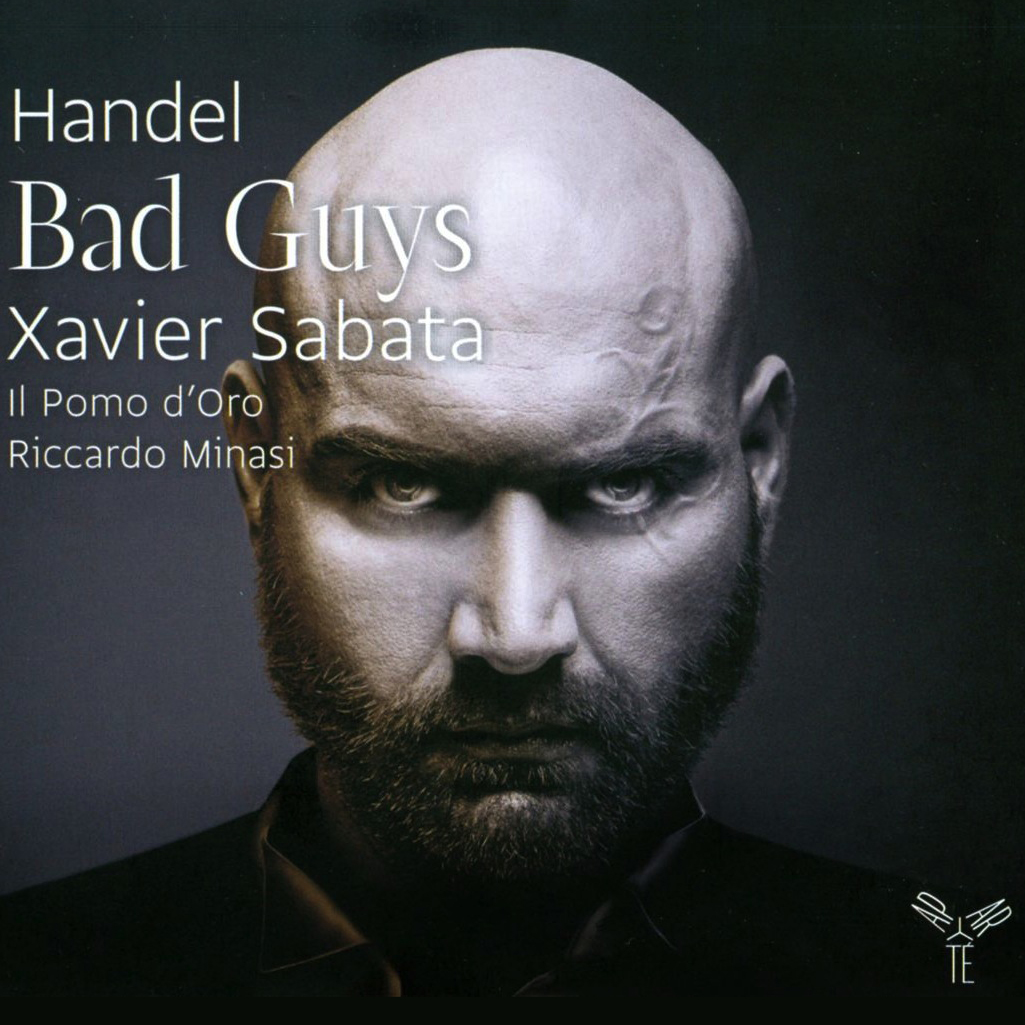

Handel

“Bad Guys”

Xavier Sabata

il Pomo d’Oro

Riccardo Minasi

(Aparte)

The castrato in Italian opera of the early 18th century had vocal power that was often associated with heroic roles, but Handel wrote several memorable villains for the voice type as well. Indeed, using the castrato’s star quality to add depth to his bad guys was one facet of his operatic genius, and the idea of collecting a group of these arias is good enough to recommend this album even apart from the vocal gifts of Spanish countertenor Xavier Sabata. And those gifts are considerable. Sabata is a true operatic countertenor, somewhat in the vein of Philippe Jaroussky (to whose album of Vivaldi heroic arias this release makes a fine companion). In addition to power and a consistently creamy tone, he has the interpretive chops to put across the emotional complications of these arias, many of which have a delicious mixture of seduction and longing: they cast the bad guy in the role of romantic pursuer. There are a few well-known pieces in here (such as those from Giulio Cesare and perhaps Ariodante), but most of the program is drawn from obscure operas, and Sabata has definitely pointed the way toward bringing them alive. The accompanimental work from the historical-instrument group Il Pomo d’Orounder Riccardo Minasi is both technically superb and fully participatory in the dramatic characterization, and the engineering, from a convent in the northern Italian town of Lonigo, exposes a venue that other recording-makers would do well to check out: it’s warm, clear, and very kind to the orchestral strings. The graphics associated with the project are of just the kind needed to draw in new listeners to this kind of recording. In all, an original and superbly executed vocal recital.

AllMusic

In his first solo disc, Catalonian countertenor Xavier Sabata joins forces with the excellent Il Pomo d’Oro in a portrayal of some of the nastiest characters to be found in six of Handel’s operas. Sabata has a warm, mellifluous voice, which tends to underplay the villainous tendencies of his ‘bad guys’. That impression is emphasised by the absence of context: there is nothing innately menacing in Adalberto’s two love arias from Ottone, for example; it is only when they take their place in the body of the opera that the dramatic subtleties of the libretto and Handel’s tonal juxtapositions illuminate the devious nature of these out-and-out rotters. From a purely musical standpoint Sabata’s recital is rewarding. His technique and intonation are flawless. His ornaments are tastefully discreet and he seems to effortlessly surmount Handel’s exacting coloratura. If this sensitive, softly coloured voice never sufficiently projects the odious nature of characters such as Polinesso (Ariodante), it may encourage readers to acquaint (or reacquaint) themselves with Handel’s complete operas, where the villains reveal their true colours.

Nicholas Anderson – BBC Music Magazine